I will be presenting a paper at the upcoming Evangelical Theological Society annual meeting in Providence in a few weeks. The topic is the discourse function of what called ‘meta-comments’. I will post pieces of the paper as I get them finished. Here is the basic idea. When people speak, they spend the majority of their time communicating what they want you to know. However, at times they step back from the actual topic and make a comment about the topic like:

- “It is very important that you understand that …”

- “I want you to know that …”

- “Don’t you know that…”

- “Of all the things that you have learned so far, the most important thing is that…”

- “If you remember nothing else that I say, remember that…”

Each of these statements has the common characteristic of interrupting what is being said in order to make an abstract statement about what is about to be said. These are all English examples of meta-comments. Here is a working definition:

Meta-comment: When speakers stop saying what they are saying in order to comment on what they are about to say, speaking abstractly about it.

Very often in narrative speeches or in the epistles of the NT, speakers will suspend what they are talking about in order to comment on what they are about to say. Examples of this include:

- “I say to you…”

- “I tell you the truth…”

- “We know that…”

- “I ask that…”

- “I want you to know that…”

These expressions are used to introduce significant propositions, ones to which the writer or speaker wants to attract extra attention. There is a litmus test for identifying a meta-comment. Can you remove the potential meta-comment without substantially changing the propositional content? Is the speaker interrupting what is being talked about in order to comment on what is going to be talked about? If it could be removed from the discourse without substantially altering the propositional content, it is probably a meta-comment. For instance, there is a great meta-comment in the movie Ocean’s Eleven just before they rob the vault, where Brad Pitt is giving Matt Damon pointers about how to conduct himself:

You look down, they know you’re lying and up, they know you don’t know the truth. Don’t use seven words when four will do. Don’t shift your weight, look always at your mark but don’t stare, be specific but not memorable, be funny but don’t make him laugh. He’s got to like you then forget you the moment you’ve left his side. And for God’s sake, whatever you do, don’t, under any circumstances…

He is interrupted mid-speech and never finishes the thought. If you remember this part of the movie, we end up laughing because we expect there to be some really crucial thing that follows, only it never comes.

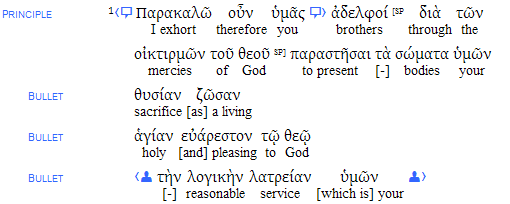

Meta-comments are used in Greek, English and many other languages to accomplish the same effect of attracting attention to something surprising or important that follows. I was told about what sounded like a meta-comment that is used in Punjabi. Just before a surprising part of the story, it is common to hear someone say “Stop ignoring me!” even if the listeners are paying attention. It interrupts the flow of the story just like a speed bump or caution sign, attracting attention to whatever it is that follows. Consider Rom 12:1:

The little symbol that looks like a speech balloon ![]() indicates the beginning and end of the meta-comment. If you have spent time in NT studies, you know that what I call a meta-comment has received a lot of attention under the heading of form-criticism. Form criticism seeks to understand a text by classifying the similarly structured or phrased portions discourse as a ‘form’, based on the function that it serves.[1] In other words, they focus on the repeated use of a specific collocation of words in a specific structure, but not necessarily in a rigid order.

indicates the beginning and end of the meta-comment. If you have spent time in NT studies, you know that what I call a meta-comment has received a lot of attention under the heading of form-criticism. Form criticism seeks to understand a text by classifying the similarly structured or phrased portions discourse as a ‘form’, based on the function that it serves.[1] In other words, they focus on the repeated use of a specific collocation of words in a specific structure, but not necessarily in a rigid order.

Critics then seek to understand the meaning of the text by understanding how the particular form was used. The meta-comments of the NT have been variously classified as disclosure formulas, request formulas, hearing forms, petition formulas, and introduction formulas. According to form-critics, it is not the context of usage that makes the form, but the formal requirements being met. Sanders states that the disclosure formula “is generally used to introduce new material, to change the subject of discussion, or when the argument takes a new tack” (1962:349). There are times when the rigidity of strictly defined forms crumbles under the weight of the counter examples that must be accounted for. There is an important difference between using ‘I say to you’ in a context where it is semantically required to understand what follows, versus using the same collocation in a context where it is not semantically required. It is the redundant usage that makes the meta-comment stand out, not just the collocation itself as a formula. [2]

Furthermore, it is not just one specific collocation of words that can function as a meta-comment. Anything that satisfies the requirements of a meta-comment can serve as one. It is not the semantic meaning of the collocation that makes it a meta-comment, it is a pragmatic effect of using the collocation in a specific context. Conversely, there is evidence that others found certain collocations accomplishing a similar form-critical function, collocations that had not been properly classified as forms.[3]

Though these collocations may be legitimate ancient epistolary forms, the fact that they are used much more broadly in ancient Greek discourse than just in letters (as well as in other languages both ancient and modern) calls for a more unified definition and description. To be continued… ___________________________________________________________

[1] Though this sounds rather simple, it is more difficult in practice. One often finds disagreement in analyses and classification of forms, e.g. “Some analyses identify vv. 13-15 as also belonging to the thanksgiving, but the disclosure formula in v. 13 and the content of these verses lead me to the identification of vv. 13-15 as a narratio that explains the background and rationale of Paul’s forthcoming visit” (Jewett et al. 2006:117).

[2] Mullins, a form-critic who sought to reign in what he considered misapplication of forms, makes the point that not every occurrence of a collocation means it is ‘form’, though he does not specify exactly what the meaningful criteria is that makes it a form versus not being one. He states, “In order to have clean distinctions, I feel we must restrict forms to pure types. Thus, 2 Cor. xii 8 would not properly be classed as a Petition. And nothing is to be gained by calling it a pseudo-Petition or a quasi-Petition. We may better say simply that sometimes phrases which resemble the form stand in lieu of a form, or that they serve the formal operation of a form” (1964:45). This illustrates the importance of distinguishing when something is semantically required versus when it is not; the former would not be a meta-comment, the latter would be since it could be removed without changing the propositional content. The fact that it is meta-discourse is what achieves the effect, it is not an inherent meaning of the phrase.

[3] Sanders makes reference in a footnote that the “word λέγω sometimes is used in place of the more prevalent παρακαλώ” (1962:353), though he does not apply this claim outside the Pauline corpus. This raises the question of whether this usage is something more widespread than an epistolary form, since they are found in the Gospels as well. Similarly, Longenecker comments, “In most of Paul’s letters there is an εὐχαριστῶ (“I am thankful”)-παρακαλῶ (“I exhort”) structure. In Galatians, however, the verbs θαυμάζ́ω (“I am amazed/astonished”) and δέομαι (“I plead”) appear and serve a similar function” (2002:184). Bruce observes that a disclosure formula is found in 1 Thes 2:1 “although here nothing is being disclosed (as in 4:13); an appeal is rather being made to what the Thessalonians already know (as in 1:5)” (2002:24). Bauckham notes regarding Jude 5, “‘I wish to remind you that …’ is superficially an example of conventional polite style (cf. Rom 15:14-15; 2 Pet 1:12; 1 Clem 53:1) but also makes a serious point” (2002:48).<–>

Great topic, Steve. Welcome to the bibliosphere. I have just posted about your new blog and linked to it from the Better Bibles Blog (BBB). I have thoroughly enjoyed the discourse studies I have done, especially those that have focused on discourse analysis of the original biblical texts.

Steve, I tried to comment on your previous post but it gave me a 404 error. I only wanted to say that I’m a huge fan of Levinsohn who has visited us twice in Mozambique for narr and non-narr and it’s a terrific topic for a blog. Best of luck!

David, I am very much a newbie when it comes to managing a blog, sorry about the comment problem. Thanks for the encouragement!

[…] Discourse Removing the mystery from discourse grammar « Introduction to Meta-comments The many faces of ‘this’, part 1 […]

I got the same 404 error when I tried to access your first blog post. I wanted to mention that Levinsohn has been revising his discourse analysis tutorial and has asked me to keep the files updated for download by others. Click here to go to the webpage from which Levinsohn’s files can be downloaded. They are the two titles halfway down the page that begin with the word “Self-Instruction Materials”.

[…] on a paper that I will be presenting at the ETS annual meeting next week. If you did not read the introductory post, I would encourage you to do so. Meta-comments are one of about 20 different devices that are […]

[…] the meta-comment that introduces the summary conclusion of the parable, indicated by . One could argue that the […]

[…] is another in a series of posts on meta-comments that began with this introduction. It is taken from a paper that I just presented to the Evangelical Theological Society, and is part […]

[…] post is part of a series on meta-comments that began with this introduction. I have discussed Gal 1:9 and Romans 12:1 so […]

[…] Introduction to Meta-comments […]