…or in other words, distinguishing between this and that.

This is a follow up post to the ones on the contemptuous use of “this”, parts one, two, and three. If you only see them when they have been co-opted for pragmatic purposes, you might get the wrong impression. It seemed prudent to let you see them in their native habitat. So get out your pith helmets and let’s do some grammar!

Do you remember learning that demonstrative pronouns (e.g. this, that) can be used as personal pronouns? We were taught to translate them (in most cases) as though they were personal pronouns like he or she. But were you ever taught why a writer would use a demonstrative. Want to know? Here we go. By the way, the framework that I use here is based on a 2003 SBL paper by Stephen Levinsohn which has not been published, to my knowledge. If you want a wonder overview of the potential contribution of discourse studies written by Levinsohn, I would strongly suggest this 11 page article from JOT.

Generally speaking, demonstrative pronouns orient you to some distinction that is present in the context, i.e. they are deictic [Update: deic•tic \ˈdīk-tik also ˈdāk-\ adj showing or pointing out directly, the words this, that, and those have a deictic function, Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, Eleventh ed. (Springfield, Mass.: Merriam-Webster, Inc., 2003). ] In the case of the Greek demonstratives οὗτος and ἐκεῖνος , the distinction is typically spatial in nature. Marking spatial distinctions represents their default or standard usage. Recall the distinction I made previously between semantic meaning and pragmatic effect. If not, read this post for some background.

The primary function of these demonstratives is to assign a near or far distinction to a discourse entity, with οὗτος used for the ‘near’ entity and ἐκεῖνος used for the ‘far’ entity. The spatial distinction may be either literal or figurative. The distinction can be seen in this simple generic statement from James 4:15.

The demonstratives are used here to differentiate two hypothetical things: this and that. The default or normal function of the demonstrative is perfectly suited to this. If you look at Matt 21:10-11, there is a question asked: “Who is this?” The answer is “This is the prophet Jesus…” It is unclear whether the speakers are actually pointing or not, but the use of the demonstrative here is deictic, singling out one individual.

Use of demonstratives in non-spatial settings

Although οὗτος and ἐκεῖνος may have the semantic meaning of spatially ‘near’ and ‘far’ respectively, they can also be used in certain contexts to bring about specific pragmatic effects, to highlight distinctions that might otherwise have been overlooked. This is particularly the case when they are used in contexts where a spatial distinction is not explicitly present. In such cases, a near/far distinction is created using the demonstrative, differentiating what is thematically central or “near” from what is of passing thematic importance or “far”.

There are certain elements in a discourse that are thematic, or that which ‘is being talked about’.[1] In narrative contexts, it is primarily the events that are thematic. There can also be a thematic participant, which Levinsohn describes as “that participant around whom the paragraph is organized, about whom the paragraph speaks”.[2]In the instructional portions of the epistles, Levinsohn claims that by default the exhortations and the addressees are the thematic focus; in the expository portions, such as in the book of Hebrews, the expository theses and the main theme of the exposition are thematic, by default.[3]

When there are other elements in the discourse that potentially compete with the default thematic element, the near and far demonstrative pronouns provide a means for the writer to disambiguate the role that these competing elements play. They provide an efficient way of marking an entity’s thematic importance. The near demonstrative marks entities that are thematic in the context.

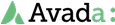

In contrast, the far demonstrative ἐκεῖνος marks entities that are not thematic in the context. For instance, if minor participants perform actions in a series of events, one might think they have become the new thematic participant, the center of attention. Use of the far demonstrative as a substitute for a personal pronoun allows the writer the mark them as athematic, meaning the center of attention remains focused on the default thematic participant. The athematic participant is only of passing interest. Consider Luke 18:14. The preceding verses are supplied for context from the ESV.

10 “Two men went up into the temple to pray, one a Pharisee and the other a tax collector. 11 The Pharisee, standing by himself, prayed thus: ‘God, I thank you that I am not like other men, extortioners, unjust, adulterers, or even like this tax collector. 12 I fast twice a week; I give tithes of all that I get.’ 13 But the tax collector, standing far off, would not even lift up his eyes to heaven, but beat his breast, saying, ‘God, be merciful to me, a sinner!’

Note the meta-comment that introduces the summary conclusion of the parable, indicated by ![]() . One could argue that the Pharisee is more distant than the tax collector, based on their last reference. Based on the point that Jesus is making, which of the two is more thematically central? From a thematic standpoint, the Pharisee is a foil against whom the tax collector is contrasted. The near demonstrative is used for the more central , which in this case coincided with the deictic reference of the pronouns.

. One could argue that the Pharisee is more distant than the tax collector, based on their last reference. Based on the point that Jesus is making, which of the two is more thematically central? From a thematic standpoint, the Pharisee is a foil against whom the tax collector is contrasted. The near demonstrative is used for the more central , which in this case coincided with the deictic reference of the pronouns.

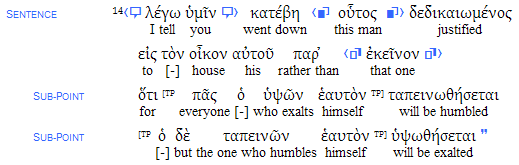

The next example illustrates the use of demonstratives in narrative proper to clarify the current center of attention, identifying which participant is thematically central. You will find John using demonstratives to this end all over the place, both in the gospel and the epistles. As noted above, there are default expectations regarding thematicity. When the writers do something potentially in conflict with these expectations, they have the option of marking these entities as either thematic or athematic using demonstrative pronouns. Consider the usage in John 1:7-8, again with some context provided.

6 There was a man sent from God, whose name was John (ESV).

9 The true light, which enlightens everyone, was coming into the world (ESV).

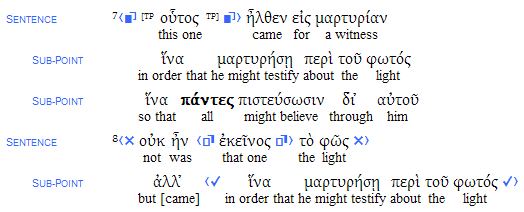

John the Baptist is only a passing thematic interest. He is marked as thematic in v. 7, but the center of attention quickly changes to the one that he came to proclaim: Jesus. “The light” in v. 8 becomes the thematic center, and John’s athematic role is made clear through the switch to the far demonstrative. Thematically speaking, John decreases so that Jesus may increase, so to speak. The symbols around the demonstratives help you to recognize the near and far distinctions when they are present in the LDGNT. They are also present in the HDNT, pictured here.

This is what I teach from at church, projected on a white board. Even though the translators have done what we were taught to do, I can still make the point about what is going on in Greek in ways that the people can understand.

One last example, as a follow up from the posts on contemtuous usage. There I noted how “this” can be used as quick way of taking something that is indefinite and does not refer to something specific (i.e., non-referential), and making it referential enough to talk about. When indefinite “this” is used in a context where the entity is well known, it has the effect of creating distance, as I demonstrated in Luke 15:30. There is similar way of creating some thematic distance by using the far demonstrative to indicate that the entity is only of passing interest. Take a look at John 18:15, where Peter and John are following Jesus to his trial. The story’s theme focuses on Peter and Jesus, yet John is there as a possible thematic candidate. Here we have another case of another John being pushed out of the thematic spotlight. Look at the kinds of terms that are used to refer to John.

Most main characters are referred to by a proper name, if one is available. One of the consequences of not referring to John as “John” is to cast him as though he were a secondary character. The italics in vv. 15 and 16 signal that there has been a “changed reference” to refer to John. Note also the adjectival use of the far demonstrative in v. 15b, another signal that he is not the thematic participant here, Peter is. All of this description about John’s connections and how he wrangled them into the courtyard could easily lead a reader to think that he is the center of attention, not Peter. By avoiding the proper name “John”, by using the athematic demonstrative, attention is kept on Peter. Even the use of the correlative ἄλλος has the effect relating John to Peter. If John is the “other” one, there must be another disciple to whom to link him: Peter. Linguistically, John is doing what this bear is doing in one of my favorite Far Side cartoons below, keeping us focused on the proper thematic center of attention.

Isn’t grammar wonderful?

The explanation in this post (and the others) is drawn from a forthcoming discourse grammar.

[1] Kathleen Callow, Discourse Considerations in Translating the Word of God(Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1974), pp. 52-53.

[2]Stephen H. Levinsohn, ‘Participant reference in Inga narrative discourse’, in Anaphora in Discourse, ed. by John Hinds (Edmonton Alberta, Canada: Linguistic Research Inc., 1978), p. 75.

[3]Levinsohn, “Toward a unified account of οὗτος and ἐκεῖνος.” Paper presented in the “Biblical Greek Language and Linguistics” Section of the SBL Annual Meeting, Atlanta, GA, November 2003, p. 2.

The last explanation referring to John and Peter at Christ’s interrogation clarifies my understanding of why John referred to himself in such a way. I always assumed he was just demonstrating humility, but you make a good case that he wants to emphasize Peter’s role (I assume because of the consequent denial of Christ). Really enjoying your posts, though I confess I had to look up what “deictic” meant.

[…] the thematic use of demonstratives, check out the series of posts that begin here, as well as the introduction to near/far distinctions. The explanation in this post (and the others) is drawn from a forthcoming discourse […]

[…] Intro to near/far distinctions […]