This post continues a series considering Porter’s claim that the Greek tense-forms are markers of aspectual prominence. As noted in the previous posts here and here, Porter construes markedness to be quantitative rather than qualitative, i.e. signaling that a binary quality that is either present or absent. This quantitative view allows him to talk about one form being more marked than another, as exemplified in the following statements:

There is no apparent evidence that in Greek any of the verbal aspects is semantically unmarked (contra Haberland, “Note,” 182). In fact, this work argues that even within the binary oppositions all members contribute semantic weight to the verbal component of the clause… On the basis of the concept of markedness in Greek verbal aspect (see chapts. 4 and 5 for treatment of the specific aspects involved), the binary pairs can be arranged in two oppositions. The perfect tense (stative aspect) is the most heavily marked formally, distributionally and semantically, and forms an opposition (see Ruiperez, Estructura, 45ff.). Within the Present/Aorist, the imperfective aspect on the basis of formal markedness, a slight distributional advantage, and semantic markedness is the more clearly marked member of the equipollent opposition with the perfective aspect (see e.g. McKay, 138; idem, “Syntax,” 46ff.; Lyons, Introduction, 314-15; cf. Comrie, Aspect, 127; contra e.g. Ruiperez, Estructura, 67-89; “Neutralization”).1

This claim comes one page after he introduces the concept of markedness, yet there is little discussion of exactly what he understands markedness to be. On p. 89 he states “the best exposition of markedness is Zwicky, “Markedness,” but without more discussion. He also cites Bernard Comrie and John Lyons to substantiate his quantificational conceptualization of markedness. Each of these linguists is studying the typology of language, looking for universal characteristics (qualities) that would facilitate the logical classification and description of linguistic features. They in no way attempt to create a ranked hierarchy. Markedness to them is a qualitative organizational strategy for identifying distinctive features. These features are then used to meaningfully differentiate members of a set. Markedness, as they use the term, is asymmetrical and qualitative. It is never conceived of as a quantity, though there are a few places where that might appear to be the case. I now present examples from each of the cited texts to substantiate my assertion.

I begin here with Zwicky’s introduction to “material markedness,” which refers to the morphological markers that distinguish one form in a paradigm from another. He states, “one set of forms contains a morpheme or sequence of morphemes expressing some category or combination of categories. If there is a parallel set of forms lacking this material, then it may be said to lack the mark.”2 He thus views the “morphological material” as a signal that some feature is present, whereas something lacking that mark does not signal the presence of something.

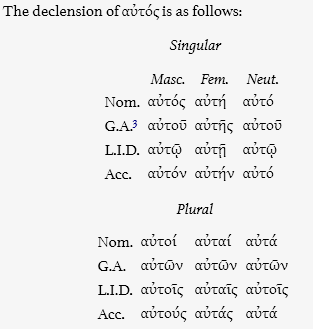

If you look at the paradigm of the third person pronoun, you’ll note that most every form has some minor difference from the other forms. The net result is to uniquely “mark” a certain set of features, e.g. case, number and gender. Everything goes swimmingly until one reaches e.g., the genitive plural forms. Note that the same form is used for all three genders. One could rightly say that this form is “unmarked” for gender, there is no signal present to specify which it is. The same kind of result is found in genitive and dative singular and plural, where there is no marker to distinguish masculine from neuter. These forms lack the distinguishing marker found on most other forms. When Zwicky talks about “material” markedness, he is referring to the phonological markers that distinguish one form from another.

If you look at the paradigm of the third person pronoun, you’ll note that most every form has some minor difference from the other forms. The net result is to uniquely “mark” a certain set of features, e.g. case, number and gender. Everything goes swimmingly until one reaches e.g., the genitive plural forms. Note that the same form is used for all three genders. One could rightly say that this form is “unmarked” for gender, there is no signal present to specify which it is. The same kind of result is found in genitive and dative singular and plural, where there is no marker to distinguish masculine from neuter. These forms lack the distinguishing marker found on most other forms. When Zwicky talks about “material” markedness, he is referring to the phonological markers that distinguish one form from another.

He goes on to state that “forms may be materially marked to various degrees,” which sounds an awful lot like he means quantity of markers, the “semantic weight” to which Porter refers. Not so much. He uses the English word lionesses as an example, claiming that it has “two material marks, one indicating sex and one indicating number.”3 He is merely pointing out that more than one marker at a time may be present. His example has the -ess gender marker on lion as well as the plural marker -s. We could make the same kind of observations about αὐτός, where there are three markers present on some forms: one for case, one for gender and one for number. Although these marks can be counted, they cannot be weighed. Zwicky and the others want to find some means of identifying the most basic forms across languages, and counting markers seemed like a legitimate method at the time.4

Now let’s take a look at his treatment of implicational markedness, by which he refers to the forms that have the “less normal or expected state” as being marked. “Implicationally marked forms will tend to show fewer irregularities than the implicationally unmarked forms … It is important to stress that implicational markedness concerns categories in general (or categories in certain sorts of contexts), rather than particular instances of categories.”5

A paragraph later, Zwicky makes clear that he is referring to categorical distinctions that are binary in nature, i.e. qualitative markers. Here there is another statement that could appear at first to offer Porter support for his notion of “semantic weight, i.e. some quantifiable amount. A careful reading eliminates this possibility. Zwicky illustrates implicational markedness using the singular/dual/plural distinction in German. The first binary distinction he makes is between -Plural (singular) and +Plural (Dual and Plural). He considers the -Plural to be the unmarked member because it manifests few markers, whereas the +Plural is more marked. One then can divide the +Plural into +Dual (marked) versus -Dual (unmarked), with markedness again determined by the complexity of qualitative markers used to distinguish one member from another. I will come back to whether Zwicky’s approach is useful (or even valid) in a later post. My goal here is simply to outline what he means by material and implicational markedness. In both instances, he is referring to the presence or absence of qualitative markers. The apparently quantitative statements refer only to complexity of the markers, not their semantic weight.

Recall that Zwicky’s goal is typological classification. He wants to figure out whether linguistic markers can be used to identify the most simple member of a given set within a given language. The hope is that such a finding could lead to some universal means of identifying such forms that would work across a host of languages. His goal is to bootstrap the classification of language features, not to quantify their semantic value. He concludes his introduction with one final point.

An important feature of this framework is that it concerns itself almost entirely with tendencies rather than strict regularities, so that there are apparent counterexamples to the principles I discuss, these resulting from the effects of the other tendencies that conflict with the tendencies relating to markedness. In pursuing my rather modest ends I disregard such complexities for the sake of exposition, though while doing so I admit that each case calls for further analysis and that the weight of these cases taken together needs careful assessment.6

This caveat makes it sound as though even Zwicky is unsure of how sound his method is, as though it is just a trial balloon. The caveats in his conclusion confirm this notion.7

Porter apparently understands Zwicky claims about markedness to be quantitative rather than qualitative. He conflates these two divergent models as though there was no meaningful distinction between them,8 Porter considers a number of factors that he feels contribute to the “semantic weight” of a form, which lead to its quantitative ranking from least marked (perfective aspect) to most marked (stative aspect). Here is what I mean. After weighing evidence regarding tense-form stem formation, tense infixes and other factors, he concludes, “In general it can be seen that the Present is morphologically bulkier than the Aorist, often evidencing double consonants or lengthened vowels.”9 The point here is that the same kinds of qualitative markers discussed above with αὐτός are essentially being added up to establish a quantifiable semantic value. His goal is to determine which member of the set is more/most heavily weighted, based on the number/complexity of “material markers.” Zwicky never makes such a claim, nor does he hold out the possibility that it could be done.

Regarding implicational markedness, Porter again weighs the various factors as though they were quantitative. “The Present/Imperfect as the more heavily marked form evidences fewer irregularites as a verbal category: e.g. ω forms overwhelmingly predominate over μι forms, unlike the diversity of weak and strong Aorists; the Aorist, regardless of its formation of the Active and Middle Voice, has an irregular formation of the Passive with (θ)ην … and the Aorist of course does not have the augment outside of the Indicative.”10

So what do these factors lead Porter to conclude? Is he looking for the simplest form for typological purposes like Zwicky? No, he is postulating a “semantic weight” based on the amount of markedness a given tense-form manifests: “The Aorist and Present/Imperfect instead comprise a bipolar opposition, with the Aorist as the less heavily marked and the Present as the more heavily marked on the basis of material, implicational, distributive and semantic criteria.”11 Twenty years later in an article on prominence, Porter affirms these earlier conclusions, relying upon the same sources used in his dissertation.12

As was the case with grounding, Porter’s misunderstanding of the literature regarding material and implicational markedness undermines two of the four pillars supporting his claims about the prominence values of the tense-forms. I will take up the other two kinds of markedness in future posts.

Return to On Porter, Prominence and Aspect

- Stanley E. Porter, Verbal Aspect in the Greek of the New Testament: With Reference to Tense and Mood (Studies in Biblical Greek 1; New York: Peter Lang, 1989), 90. Italics mine. [↩]

- Arnold M. Zwicky, “On Markedness in Morphology,” Die Sprache: Zeitschrift für Sprachwissenschaft Wien 24, no. 2 (1978): 130. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Zwicky, Lyons and Comrie attempted to count markers as a metric for judging complexity, but do not translate this to a claim about semantic weighting. They simply focus on complexity. Several recent papers by Martin Haspelmath shatter any notion that such counting is a credible approach. Edna Andrews does the same with frequency/statistics in her chapter “Myths about Markedness.” See Martin Haspelmath, “Against Markedness (and What to Replace It With),” Journal of Linguistics 42, no. 01 (2006): 25–70; Haspelmath, “Frequency Vs. Iconicity in Explaining Grammatical Asymmetries,” Cognitive Linguistics 19, no. 1 (February 2008): 1-33; Edna Andrews, Markedness Theory: the Union of Asymmetry and Semiosis in Language (Durham: Duke University Press, 1990). Porter curiously cites two of these works in his most recent paper on prominence, neither acknowledging nor engaging their arguments against his claims. His citation of Andrews in note 37 makes it seem as though it lent favorable support toward his methodology. (Porter, “Prominence: An Overview,” pp. 45-74 in The Linguist as Pedagogue (ed. S E Porter and M B O’Donnell, Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press Ltd, 2009), 55 n. 36, 56 n. 37. ) [↩]

- Ibid., 131-32. [↩]

- Ibid., italics mine. [↩]

- In his conclusion Zwicky observes that “I have chosen to treat as different senses of markedness what many have seen from the outset as manifestations of a single phenomenon. Indeed this is the spirit in which Greenberg, Sehane, and Comrie approach the subject, as do the writers they build their discussions on.” (“On Markedness, 142.) Zwicky’s different senses of markedness were thus not independent means of corroborating a claim, but were simply different factors by which the most basic and simple form—an asymmetrical, qualitative default—could be identified for typological purposes. See Haspelmath, “Against Markedness,” for arguments against viewing such subdivisions of markedness as legitimate. He argues that they are all derivatives of frequency or other contextual factors. Hence, they do not provide the four independently corroborating factors that Porter claims. [↩]

- I spoke with Porter in person about this issue of conflation on the last day of 2009 SBL Annual Meeting in New Orleans. I wanted to make sure I was not misunderstanding his view. He stated that he did not see a meaningful distinction between these two approaches of markedness. His recent article on prominence does much to confirm this view. He appears to have read the qualitative claims from the linguistic literature as quantitative. This means that some of the most crucial claims of his thesis are based upon a flawed understanding markedness. [↩]

- Stanley E. Porter, Verbal Aspect in the Greek of the New Testament: With Reference to Tense and Mood (Studies in Biblical Greek 1; New York: Peter Lang, 1989) 180. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Ibid., 181. [↩]

- Stanley E. Porter, “Prominence: An Overview,” in The Linguist as Pedagogue (ed. Stanley E Porter and Matthew Brook O’Donnell; Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press Ltd, 2009), 56. [↩]