Within NT studies the notion that the Greek verb lacks tense/temporal reference has become fairly accepted. If we compare this tenseless view of Greek with what has been claimed by every linguist and grammarian Porter cites in his research, you might scratch your head a bit. Why? Not one of them argues that Greek lacks tense. The linguists like Lyons, Comrie, Wallace and Haspelmath treat Greek as a mixed system with tense, aspect and mood all present in the indicative.

If it is true that the broader field of linguistics has treated Greek as having both tense and aspect, where did the “tenseless” idea come from? Why did it come about? I do not really know the whole story, but it seems that Porter was seeking to account for the incorrect claims of mainly commentators–not grammarians1–some of whom treated Greek verbs as though they had absolute temporal reference. It also seems that he was seeking to set his work apart from what was becoming a crowded field, claiming something no one else had claimed before, viz. that the Greek indicative lacked any temporal semantics.

But again, why was there a need to claim a total lack of temporal reference? In my last post I highlighted the areas of significant consensus between Porter and myself. However, Porter added two significant claims to his dissertation, claims not found either in biblical studies or in linguistics: a tenseless view of the verb and a semantic weighting/prominence view of the verb. Both of these proposals lack support or motivation from the field of linguistics. They are essentially rhetorical inventions originating from Porter’s dissertation.

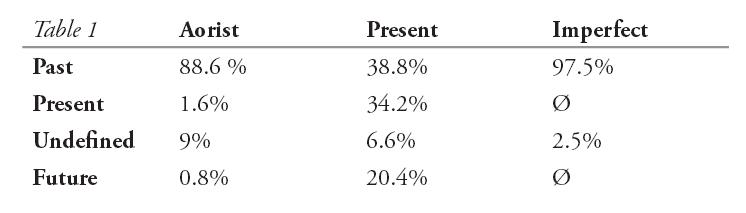

The basic premise of the timeless view is to not just argue against the presence of absolute time/tense in the verb in favor of aspect. Rather it completely rejects the notion that the Greek verb conveys any temporal semantics in the indicative. The most compelling data for this is the multivariate use of the Present, attested by the statistics gathered in Decker’s Temporal Deixis of the Greek Verb in the Gospel of Mark with Reference to Verbal Aspect. Note the almost equal distribution of the present tense-form in past, present and future temporal contexts, not to mention the timeless/atemporal uses, cited from my HP article (p. 215):

As you can see, the Present tense-form shows the most damning distribution when it comes to the traditional understanding of it referring to present time.

If you have read much of my work, you will have heard me harp on the importance of one’s theoretical framework. This lesson was thankfully beaten into my head by Larry Perkins, Stephen Levinsohn and Christo Van der Merwe; it has saved me from ruin on a number of occasions, and held the key to unlocking sticky problems. The strange distribution of the Present indicative is one of them.

There are two widely accepted principles that were ignored by Porter and those who have adopted his model. The first is the fact that most every Indo-European language–which would includes English, Greek, German, etc–has what linguists call a past/non-past distinction, rather than the past/present/future distinction presupposed by Porter. This means that the Present tense-form in these languages doesn’t exclusively refer to the present, but rather more broadly to the non-past.

For example, I could say “I am eating dinner with Bob [Monday]” and have either a present or a future meaning depending on the presence or absence of the adverb “Monday.” So too with Greek. This means that the “futuristic presents” are not anomalous, but are behaving like a good Indo-European language would be expected to behave. The failure to incorporate a past/non-past principle into his framework led Porter and those who have followed him to misconstrue the data.

The second principle missing from his framework was treating the historical present as a pragmatic usage rather than as prototypical. The numbers above treat the past use of the Present as though this is part of its basic semantic meaning, rather than as a pragmatic highlighting device based on the mismatch of tense and aspect to the narrative context.You’ll need to read the paper for the full argument.

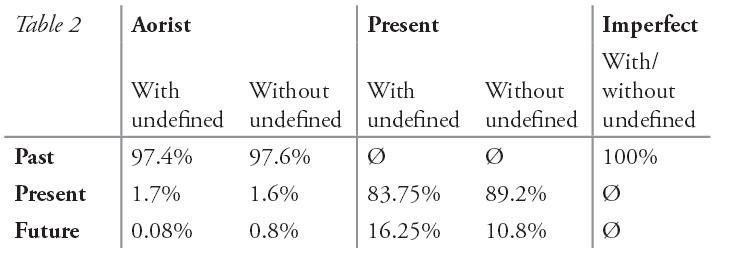

Recognizing the past/non-past distinction, and treating the historical present as a pragmatic device–just as both traditional grammarians and linguists have done for decades–changes what originally seemed like a mess into something quite a bit tidier. Here is the updated table from my article.

- The HP usage is excluded, based on it not representing the basic semantics of the Present.

- The future reference is part of the core semantics, based on the non-past reference.

- The temporally undefined data tells us nothing about the temporal reference. It says the form was chosen based on the aspect that it conveyed in a timeless/atemporal context. It should thus either be included in the core usage, or excluded as not telling us anything about temporal reference.

In either case, the Present indicative forms in Mark render a 99% consistency in usage with what would be expected of an Indo-European tense form.

So had the widely-accepted linguistic notions of Greek having a past/non-past temporal distinction and of the historical present being a pragmatic usage been incorporated into Porter’s theoretical framework, there would have been no basis for making a tenseless/timeless argument in Greek. There likely would not have been much of a Porter/Fanning debate, and our field would not have squandered the last 20 years arguing about a linguistically unsound proposal.

One’s presuppositions play a huge role in determining outcomes. Beware.

Hey, it’s those 0.8% of future-referring aorists that make this field so fun!

I’m interested in so-called gnomic aorists. Do you have explanation for those? Do they belong to the “temporally undefined data”?

Nice post, Steve. I’m also interested (along with Eeli) in the “so-called gnomic aorists”. I’m probably way off – not having researched it *at all*, but I’ve been wondering about whether “gnomic-ness” may be the essential quality of the aorist. An idea that occurred to me with your analysis of the HP.

Thank you. If your goal is to speak to the non-specialist, you have succeeded with this non-specialist reader. I was particularly pleased to discover that this understanding of the Present jibes with what I had been concluding from the forms of Greek, that it is “non-past.” It makes me think that the Greek term for “present verbs” is better: ἐνεστώς. The “Present” tense just “sits there / stands there / is present.” It doesn’t have a lot to say about itself.

I don’t know what English word would match ἐνεστώς, but it would be better to use it. Even more helpful is using παρατατική instead of “Present” when talking about aspect. “Present” infinitive, subjunctive, or imperative doesn’t even make sense. I wonder if there is an English word in vogue for παρατατική.

Dr. Runge,

First, as a layman, I want to thank you for your Discourse Features work, as I have learned a lot from your approach. And your distinction here between only past and non-past really simplifies things! In fact, it simplifies a defense of Porter’s non-temporal position.

In English, for example, we won’t find the past tense-form in a non-past context (though we can find the present tense-form for both non-past and past, with the latter a device to illustrate vividness). It is strictly a past-time form. Yet, in NT Greek we find the aorist, the present, and the perfect in both past and non-past usages. Even the imperfect, often assumed to be a strictly a preterite, can be found in non-past, e.g., Colossians 3:18, Galatians 4:20. This indicates that something other than the form itself defines temporal reference.

As for Porter’s assertion that the HP is a prominence marker, it’s important to note that he stresses that it’s the author’s subjective choice to use this device. Luke apparently did not care for it. John used it copiously. And each writer uses the HP a bit differently. Here are some usages (according to Porter, Fanning, Decker, S. L. Black, etc.):

(a) To begin a new pericope

(b) To begin a specific scene after a general introduction

(c) To introduce new characters

(d) To illustrate a character’s movement to new locations

(e) To highlight following events (cataphoric function)

(f) To close a pericope

Mavis Leung’s work in the following re: John’s use of the HP is important:

http://www.etsjets.org/files/JETS-PDFs/51/51-4/JETS%2051-4%20703-720%20Leung.pdf

…um, I meant Discourse Grammar…

Dr. Runge,

I’ve reread your section of the HP in Discourse Grammar, and read more completely your “Discourse Studies and Biblical Interpretation.” It seems your most recent work has refined your earlier one. Now I have a better understanding of your position. I perceive that it may be able to eliminate Porter’s position of the future as “aspectually vague,” as the future does seem to be perfective, but encoding future temporal reference (as per Fanning and Campbell). In part with that in mind, I’m still processing your combined aspect/tense position.

However, with all due respect, I do wish to make a few comments on your criticism of Porter in your “Discourse Studies and Biblical Interpretation.” I know this is a sensitive issue for all parties involved, so I hope my comments here convey the neutral tone I’m intending. I apologize in advance for the length, which seems necessary to explain and defend Porter. On p 198, you write:

Yet Porter does explain that the non-remote feature of the present is the reason for his assertion that the present is more heavily marked (without any qualification, so this would include narrative, i.e. the HP). Porter uses non-remoteness [-remoteness] (VAGNT p 95; cf. chart on 109) in his description of the semantic/aspectual value of the present in comparison with the more remote imperfect [+remoteness] (with the aorist even more remote – the “helicopter” view); and it is this non-remote quality that makes the HP stand out in narrative (see VAGNT p 207, last paragraph). He compares the present with the imperfect, stating of the imperfect, “in relation to the formally and functionally marked Present…” (bold added), thus emphasizing the morphological form (which encodes [-remoteness]) of the present as part of his analysis, where function follows form, with the imperfect “used in contexts where the action is seen as more remote than the action described by the (non-remote) Present” (p 207; Porter capitalizes tense-forms).

Moreover, in quoting McKay – upon whose work Porter builds – he addresses the past/non-past distinction of IE languages (p 207), and he specifically addresses the issue you cite re: the English present continuous tense in another work (“Tense Terminology and Greek Language Study: A Linguistic Re-Evaluation”, in Porter, Studies in the Greek New Testament (New York: Peter Lang, 1996), p 39; which first appeared in 1986.), using the example of “I am going to the mall tomorrow” as indicating future use of the present. For those who don’t have ready access to VAGNT, it seems proper to quote him at some length (p 207):

In addition, Porter is clear that, in his terms, εἰμί is “aspectually vague” (like all -mi verbs; see VAGNT pp 442-447) because it doesn’t offer perfective or stative aspects, and hence, does not figure into Porter’s scheme of aspect or prominence; therefore, your example of Romans 1:25 does not counter his claim of prominence. You note, correctly of course, that “the usage is more likely motivated by the semantic requirements of the context” (p 198).

Hi Craig,

From an apologetic standpoint, Porter has indeed produced a logically plausible theory of verbal aspect, one where there is no need for tense. This is not the point I am arguing against. In this sense, your points above are valid. One can indeed use spatial terminology in lieu of temporal ones to explain Greek or English usage. This is essentially Campbell’s position, and I am able to reformulate my model in his terms and reach a basic consensus. My disagreement with Porter’s claims is not his spatial metaphor, but how he arrives at claims of prominence. How does the prominence model he advocates compare to the larger linguistic discussions on the matter? And by linguistic I am not talking about discussions within NT studies, but in linguistics proper. As you read the broader literature, you’ll find that Porter’s claims contradict foundational principles, jeopardizing the linguistic viability of his model. One piece of this discussion concerns whether Greek is really tenseless or not. It is interesting that although Lyons allows for a spatial model in theory, he opts for a temporal one in practice. Furthermore, if you read the balance of his volume, you’ll find Lyons treats Ancient Greek as a tensed language, with a past/non-past distinction.

For reasons that I do not fully understand, Porter has been determined to argue for a timeless verb system in Koine Greek, going against foundational linguistic principles in the process. He builds an apologetic case for it, selectively citing the linguistic literature rather than fully engaging it. Representing Lyons as though he advocates a spatial view, when in fact he treats Ancient Greek in traditional tensed terms is a good example of this. Others are described in my article critiquing Porter’s use of contrastive substitution. He does more than simply argue that space offers a more viable description of the verb than time, as Campbell does. He argues for the complete absence of temporal reference in the verb.

I have time to engage in a running debate on these matters. I have presented my misgivings about Porter’s claims in papers and articles, and you are free to reject them if you find them unconvincing. The issue I am pursuing is how Porter’s claims compare to the broader linguistic literature. My arguments against his position are derived from the very same linguistic books and articles Porter has selectively cited as support. In apologetic terms, Porter has proof-texted his argument in my view, using linguistic claims and principles without regard to their broader context. So although his model is theoretically and logically convincing, it is unsound from the broader standpoint of linguistics.

I wish you the best on your research into these issues, and thanks for the comments.

Dr. Runge,

Thanks for your response. I’ve been reading your material this weekend (sorry, I’ve just learned of your critique of Porter), and, though I have no real background in linguistics, I am beginning to grasp your criticisms of Porter’s theoretical basis. I read the article you reference in your comment above on ‘contrastive substitution,’ so I’m gaining more familiarity (slowly).

I can fully understand the fact that you are busy, but, more importantly, I appreciate your willingness to post the material in a manner that the layperson can 1) actually find easily, and 2) apprehend somewhat easily.

I can see how Porter seems to have not clearly defined and/or misapplied prominence; but, from my perspective, if things are viewed primarily (if not strictly) from a spatial perspective, then the present tense-form is prominent by virtue of its proximity to the event/situation. From this perspective then its use as an HP is not exceptional (though it doesn’t seem to reflect the continuous nature usually found in the imperfective). I think this is what Porter was getting at, by reading between the lines of his material (his purported misapplication of sources notwithstanding).

This leads to something I’ve been chewing on. If the present (normally) encodes non-past, then I’m assuming the aorist (and imperfect, pluperfect) encodes past time. With this in mind, and applying your position that the HP is marking prominence due, in part, to its ‘wrong use’ of temporal reference, then, applying this principle to the other tense-forms, e.g., wouldn’t a non-past aorist signal prominence? I don’t think this is the case, but this, to me, seems to be a logical implication of your position on the HP.

I think you’d agree that an instance of a non-past aorist would not signal prominence, hence, I think that an understanding of it (as with the imperfect and pluperfect) as remote works better. With this thought, a future aorist, e.g., would merely be using its perfective aspect (the most remote view, as from the helicopter) to report the event/situation as a whole. Similarly, an imperfect in a non-past context would be remote as compared to a present (though not as remote as the aorist/perfective), and hence provide supplementary details (such as in Col 3:18).

I won’t be offended at all if you choose not to comment. I offer this in case a reader wishes to engage in the discussion. I have a tendency to over-analyze at times, and I may well be doing that very thing here. I’m just searching for understanding.

Hi Craig! What examples of a non-prominent, non-past (finite) aorist do you have in mind?

Stephen,

Just to be clear on my position, an aorist is a simple description of an event/situation. In English, it’s akin to the simple past tense, e.g.: She waited. I studied, or the simple present tense: he eats etc. It usually carries narrative in Koine Greek.

The aorist is assumed to be a past-time tense-form, most deem so because of the augment; hence, a usage of the aorist in non-past would be exceptional, and the stats bear this out. Being non-prototypical, wouldn’t this indicate some sort of prominence as compared to a past usage, by applying the same reasoning Runge is to the HP?

If this is so, then the following should indicate prominence:

Luke 8:52 (she is not dead but sleeping); 1 Corinthians 4:18 (some are arrogant/puffed up); 2 Corinthians 5:13 (if we are out of our minds); 1 Peter 1:24 (the grass dries up and the flower falls (off)); John 13:31 (Now the Son of Man is to be glorified and God is to be glorified in Him) – some may call this latter one present tense rather than future, but the future form in the next verse seems to indicate future temporal reference.

It also should be noted that Campbell agrees with Porter’s position on the non-temporal indicative, as evidenced in the his Basics of Verbal Aspect in Biblical Greek (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2008):

“I follow Porter and Decker on the issue of tense [time]: it is not regarded as a semantic value of verbs in the indicative mood” (p 32; brackets mine).

Thanks for those examples, Craig. Two of them look past to me (Luke 8:52 οὐ … ἀπέθανεν “she did not die” and 1 Cor 4:18 ἐφυσιώθησάν τινες “some got puffed up”), and 2 Cor 5:13 is counterfactual, a different issue. As for the others, I would say that I don’t understand what role prominence should or should not have had in those examples.

Stephen, thanks for your response. I wanted to provide more than one example, as I understand others may view a past temporal reference for some (though note that the default ESV hyper-link in the comments section here indicates present temporal reference for both examples you see as past – most translations, save the NASB, indicate present time for Luke 8:52).

My point, which I may not have made clear, is that if the HP denotes prominence in part because of its ‘wrong’ use of temporal reference (past instead of non-past), then why wouldn’t a ‘wrong’ use of the aorist, i.e., non-past usages, encode prominence of some sort? If they do not, which is how I see it – and it seems you do as well – then why would the HP signal prominence by its ‘wrong’ use of non-past?

I didn’t cite Mark 1:11/Luke 3:22 (σὺ εἶ ὁ υἱός μου ὁ ἀγαπητός, ἐν σοὶ εὐδόκησα – I am well-pleased), because it is timeless (Porter’s definition because there are no deictic indicators to place it definitively on the timeline – but this agrees with Robertson), though I don’t think anyone would argue that it’s either non-past, or perhaps past + non-past. Once again this is a ‘wrong’ use of the aorist, and I don’t see this as indicating any sort of prominence (not that the statement itself is not very important!).

It is for this reason that I think that using “remoteness” to describe the augment’s function works better. That is, if we see the imperfect as remote from the present, the pluperfect as remote from the perfect, and the aorist as the most remote of all (the helicopter view, as per Isachenko, as cited in Porter, VAGNT, p 91), then prominence of each individual tense-forms is due to relative proximity to the event/situation (parade, as per Isachenko’s example).

I’m not suggesting I have this all figured out, with respect to the inter-relationship of all the forms, but it makes more sense to me than selectively using the HP as a prominence marker primarily due to its ‘wrong’ use of temporal reference (past as opposed to non-past). With this view of remoteness/proximity, the more proximate forms are naturally more prominent. The aorist merely provides a complete (not necessarily completed</b)) view, an overview of the action/situation, while the others are closer to it illustrating continuous action, providing details, or other signals of prominence (that is, being 'closer' to the even/situation). This is how I read Porter's scheme, again, whether or not he's proof-texted sources, readapting linguistic terminology (and I'm not suggesting he didn't, as I've no reason to doubt Runge's peer-reviewed work in this regard).

Setting aside the stative aspect, since it is not a settled matter anyway, the imperfective aspect would always be more prominent as compared to the aorist, due to relative proximity, with the present more so than the imperfect because of the present's closer proximity to the event/situation.

One example of present/imperfect together would be Colossians 3:18, in which the present imperative (gnomic/omnitemporal) in the main clause is coupled with an imperfect (gnomic/omnitemporal) in the subordinate clause, with the imperfect providing supplementary details. This illustrates that the more remote imperfect is less prominent.

I don't want to seem like I'm criticizing Runge's work in general, for, as I've stated in the very first comment, I've learned a lot from Discourse Grammar. My only point of departure at this juncture is the treatment of the HP. Maybe my whole thinking of applying this same methodology to the aorist is off-base; i.e., perhaps there’s a better explanation for the ‘wrong’ temporal use of the aorist.

Thanks for your comments, Craig.

Regarding Luke 8:52, ἀπέθανε is an aorist, and there is nothing amiss with a past reference in the context. The fact that some English translations prefer “she is dead,” which is really a more appropriate rendering of a perfect τέθηκεν (cf. v.49), is not really telling; that has more to do with English style in trying to coordinate two verbs of different tense with the same subject pronoun (or perhaps even a holdover from the Vulgate’s non est mortua). The NASB goes for “she has not died,” but an anterior perfect in English is a perfectly fine translation for many aorists, especially in this context where the reference time for her dying is pretty clear (i.e., between the time Jesus was told about Jairus’ daughter and the time he arrived).

As for the HP, I don’t view the semantics as “wrong,” though its context arguably is. I hold that its use in a strongly narrative context forces, among other things, a “deictic shift” to interpret. This deictic shift requires more cognitive resources than the aorist to effect, and it is at this point I link up with Steve and see it as a highlighting strategy. There is also considerable authorial variation in how the HP is actually used.

As for the prominence of non-past referring aorists, I confess I don’t really understand what you mean by “prominence.” Perhaps you could explain. All the special things about the HP are basically effects in narrative, because the present is not a narrative tense, while the aorist is. All the non-past referring aorists (except for those I objected to) are in non-narrative context, so I would expect different effects to happen. For me, a gnomic use of an aorist is pretty marked, so I don’t understand why you seem to think that 1 Pet 1:24 isn’t prominent, whatever that means to you.

Eventually, I’ll have something to say about Mark 1:11, but not now, it is too premature for me at the moment.

As for Porter’s scheme, there is no real dispute that I’m aware on the aspectual meanings. But it is also clear that there are twice as many forms than the three aspects would allow, and everybody needs to have an explanation for the difference between the imperfect and present, between the pluperfect and perfect, not to mention how the the future and aorist fit into the picture. And it is here where Porter’s proposals are viewed as problematic. Normally, imperfectives are thought to provide the background while perfectives the foreground: “I was reading when the cat came in.”

As for Col 3:18, is ἀνῆκεν imperfect or perfect? And how can you tell?

Stephen,

Thanks again for your response and your comments. As for Luke 8:52, while it may be taken both ways (past or present), I contend that a present temporal reference “is not dead” is the best translation because of the present indicative “sleeps” (or “is sleeping”) which follows. Of course, we can’t very well translate the aorist as “is not died,” (or “was not died” for past) as that would be bad English – hence, the various English translations – but that’s the sense of the aorist if it’s rendered with present temporal reference. This seems right to me, as Jesus appears to be using καθεύδει both euphemistically and rhetorically, for obviously she was dead (had died) and was subsequently resuscitated/resurrected by Him.

Regarding the HP, with you, I don’t think its aspect is ‘wrong’ (I don’t think it’s ‘aoristic,’ or acting perfectively), but perhaps for a different reason. This goes back to its non-remoteness/proximity (as compared to its remote counterpart the imperfect, but even more so than the aorist, which is the helicopter view). It is this semantic value of proximity/non-remoteness that provides its ‘prominence.’ I understand this usage may differ from linguistics, but I’m just applying Porter’s views. (I also understand that Porter has foreground/background flipped as compared to linguistics.)

So, from my perspective, which follows my understanding of Porter, the present tense-form

1) Semantically encodes imperfective aspect, with the added property of non-remoteness/proximity, in distinction from its aspectual partner, the remote imperfect. This proximity to the event/situation provides its ‘prominence,’ no matter the temporal sphere of reference. This is its sole semantic value.

2) Neither absolute tense nor relative tense are semantically encoded (in any tense-form). That is, temporal reference is a pragmatic implicature, based on context, and possibly lexis. This better accounts for the complete variety of temporal uses of not just the present but the variety of usage of all the tense-forms (excepting the future).

Under this schema, the HP is prototypical with regard to temporal reference (since tense is not semantically encoded), rather than exceptional. Then it’s the present tense-form’s proximate value that denotes formal ‘prominence,’ thus providing its functional ‘prominence’ in a past-time narrative setting, in aspectual opposition with the aorist/perfective. This ‘prominence’ also provides the highlighting. Now, of course, there’s still debate on just how this works out in the various contexts, as, just like you noted, each author uses the HP in differing ways.

Also, in my view, one temporal reference in any of the tense-forms is not more or less prominent than another. A gnomic present is not any more prominent than a past-referring present (HP). And the perfective aspect, as the most remote of all the tense forms, is the least marked.

Not that I’m trying to promote my website, but I’ve been writing a series of articles explaining Porter’s perspective, and the most recent one contains three figures which graphically illustrate and explain this remoteness/proximity issue (and see the relative footnotes). Just click on my name and you’ll see the current article.

I’m not sure what you’re driving at with ἀνῆκεν, but the sources I quickly queried do not question that it’s an imperfect (BDAG, which refs BDF in this regard, Robertson, Campbell, Porter, Decker).

Thanks for your comments, Craig, and the shameless promotion of your blog. It’s pretty interesting; I’ve added it to my feed reader and I may move the discussion over there if it’s OK with you.

Still regarding Luke 8:52, I think it’s important to keeping in mind Porter’s caution: “Failure to make a translation distinction does not minimize semantic value or contrast.” Porter, Verbal Aspect (1989), 265. As you know, translation is a form of interpretation but there are often countervailing considerations in rendering a text, especially stylistic, so translations have to used with care. Semantically, there is nothing against a past, and in fact “died”, “has died,” and “is dead” all denote the same event in terms of propositional truth value but they focus upon different facets of it. Personally, I see a double contrast in both time and event (dying vs. sleeping), but if one really wants to insist on a common reference time that covers the present, then an anterior rendering of the perfect per the NASB works fine too: “she has not died.” In the Greek present can also support an English perfect progressive, so we can neutralize the contrast even further for stylistic reasons: “she has not died but has been sleeping.” In any event, I don’t see Luke 8:52 as a clear example of a non-past reference, particularly since the girl was thought to have died in the past.

As for “prominence,” I don’t really have a grip on what you mean by it. Personally, I don’t find the term terribly helpful, and the term as used here seems vague and/or equivocal. We have an HP in English, which is a tensed language, and I contend that the Greek HP works basically the same way. (There is a slight adjustment for aspect, of course, but that’s not a problem.) There’s no need to bring in another theory to explain the HP if the tense theory is already adequate to do it.

I hope to write something up on the difference between tense and proximity/remoteness that takes into account developments in linguistics since 1989. I am aware of Porter’s claims about tense in Greek, but the problem is that Greek is not sui generis in this regard, and many “tense languages” behave the same way in material respects. So if Porter is right about Greek, then everyone else is wrong about English, French, German, Swedish, etc. And vice versa.

I’ll check the references for ἀνῆκεν, but it seems to me that the perfect and imperfect have the same form, albeit with different temporality (aspect and/or tense). The perfect may fit the context better.

Stephen,

Sure you may take the discussion over to my blog, as I’m thinking we have, at least in part, departed from the subject of this thread a bit.

I’ll concede (as I’ve pretty much stated before) that Luke 8:52 can be interpreted either as present or past, but I think the various English translations, which, presumably, have NT Greek scholars on the various translation committees, predominantly render this in the present is telling. Decker has stated that the NASB tends to strongly favor traditional grammars’ tense categories such that an aorist is almost always (if not always) rendered past, a present is rendered present, etc. (his exact words: “a very mechanical translation of tenses without much regard for context” from footnote 24 here). While the NASB is a more literal translation, it seems noteworthy that the ESV, which has the same basic thrust as a literal translation, renders it present.

I suppose I’m using ‘prominence’ as akin to ‘markedness.’ But, here’s where I should probably provide full disclosure. I’ve stated, or at least hinted, that I don’t have a background in linguistics, as my knowledge has come indirectly from Porter, Decker and Campbell, and a few other sources with more of an NT emphasis rather than linguistics generally. Moreover, I have no formal training in Koine Greek, having only self-studied. Perhaps I’ve gone about it a bit backwards as I’ve learned only the bare rudiments of NT Greek, then jumped to learning more advanced grammar (which improved my English skills in this regard), then focused on NT/Koine Greek verbal system, primarily because I’ve been wanting to uncover the real meaning of the Greek perfect.

Regarding the HP, the HP in English has, the way I see it, quite a different function (which I mention in a footnote in part 2 of the series) than Koine. It is a total temporal transfer to effect vividness of the event/situation. In a similar way the English use of the past tense-form for present (“Did you wish to speak with me?”) is a polite idiom, but even that could be argued that past tense is in mind, for in the example provided it’s clear that the individual is asking based upon a past understanding that the person queried may well have been looking to speak with him/her. The response to the question could be “Not any longer, I’ve figured out the answer.”

I’m unclear how if Porter is right in his non-temporal theory that this renders tense-prominent languages (at least those which use aspect periphrastically such as English) wrong in some way(s).

OK, Craig. While we’ve been debating the temporal reference of Luke 8:52, it also important to realize that the rendering of ἀπέθανεν as “is dead” also gets the aspect wrong. The expressing “is dead” in English refers to a (result) state, whose aspectuality is imperfective. A perfective rendering for achievement verb like “die” would be “die(d) (right now)” or something like that. I can only conclude that the ESV and other translations departed from the author’s “reasoned subjective choice” (as Porter puts it) as to aspect for stylistic reasons particular to the target language.

Stephen,

I’ll quote Porter (VAGNT), as he identifies it as present usage: “οὐ γὰρ ἀπέθανεν ἀλλὰ καθεύδει (she is not dead but sleeping), where the difference in verbal aspect is clearly seen; the author contrasts the condition of deadness with her being in progress sleeping, with the stress falling on the latter” (227, parenthetical translation Porter’s). Just like your preference to construe this as past mandates an English past perfect in translation, an English perfect is necessary to translate as present temporal reference. The way I see it, to render it literally in past would be “was not died,” while in present would be “is not died,” both of which are bad English, thus requiring use of some form of the English perfect in either case.

In the same paragraph as referenced above, Porter lists a number of other present-referring aorists (Matt 23:23, tithe and disregard; Matt 25:24 know; Mark 3:21 he is out of his mind; Luke 2:30-31; Luke 4:34; John 7:48; John 11:14; John 11:14; John 16:30; Acts 7:52), and more still are on the following page.

I was reading Campbell’s Verbal Aspect through more completely (I skimmed portions previously, relying mostly on his Basics), and noted that he is in agreement with my position of remoteness being a better way to construe the augment as compared to it being a preterite marker (he argues this over against one of his mentors, T. V. Evans, on pp 88-91). Moreover, he argues that remoteness is a semantic value of the aorist, imperfect and pluperfect, as opposed to past tense, as this better accounts for those ‘exceptions,’ i.e., those instances in which these forms are used in non-past contexts.

My disagreement with Campbell is his all-encompassing explanation for the HP as “the imperfective-proximate spill from discourse” in narrative contexts. I agree with this overall conception that the present tense-form is a proximate form (as opposed to the remote imperfect, and the even more remote aorist), and that this is what provides a sort of markedness/prominence, but I disagree re: λέγω, as this may well be a ‘stereotyped idiom,’ as S. L. Black (referencing Fanning) has stated.

I’ve just ordered copies of Comrie’s Tense and Aspect, as well as Lyons’ 2-volume Semantics to get a better handle on linguistics. (As a layman, I don’t have access to a decent library, so my own personal library becomes my source of info.)

The main issue for translating the verb ἀποθνῄσκω into English is its necessarily punctiliar quality/nature.

In reading Comrie’s Tense I’ve found verbiage to affirm Porter’s overall thesis of non-temporality, a viewpoint which can rightly be applied to most any language:

…While much traditional grammar regards tense as a category of the verb, more recently it has been argued that tense should be regarded as a category of the whole sentence, or in logical terms of the whole proposition, since it is the truth-value of the proposition as a whole, rather than just some property of the verb, that must be matched against the state of the world at the appropriate time point (p 12).

Yet, in all fairness I must include a portion of the paragraph immediately following the above:

Even more recently, however, there have been suggestions that the earlier analysis, assigning tense to the verb, may be correct, though for reasons that were not considered by those who set up the original model. The reason is that the noun phrase arguments of the verb are very often outside of the tense, whereas the verb is necessarily within the scope of the tense… (pp 12-13).

However, even here it must be conceded that additional words outside the verb can and do signal temporal reference, thus clarifying the tense of the verb. Consider the following:

Jane calls Jill: “What are you doing?”

Jill: “Driving. I’m going to the mall.”

In this conversation we can be assured that Jill is in the process of going to the mall right now, as the context makes it clear. Yet, as Runge has noted, by itself the sentence “I’m going to the mall” is ambiguous with regard to temporal reference, as it may be a current or future action that is in mind:

Jane: “What are you doing tomorrow morning.”

Jill: “I’m going to the mall.”

Deictic indicators make all the difference, though, yes, one can argue that it’s the verb that carries the idea of tense as clarified by deictic markers. But then doesn’t this make relative tense a pragmatic function rather than an inherently semantic one? I think the argument on both sides boils down to semantics, using the term in its general, non-specific linguistic sense.

Moreover, if the aorist is a past tense form, then how do we explain Mark 1:11, e.g.? No one will argue for “I was well pleased” in this context. As Porter asserts, the proposition is best viewed as timeless, because there are no specific deictic indicators to define temporal reference. It may strictly be the present (but then what about Mat 17:5, II Peter 1:17?), it may be past + present, or it may encompass the entirety of the Incarnation. The point is that this is not past tense or not merely past tense. Thus, it’s not fair to Porter’s or Decker’s work to discard this verse by placing it in the “undefined” category, as it’s an important example used by both to affirm their positions.

Incidentally, in the very first Comrie quote he references Lyons’ Semantics, which, since I’ve procured a copy, I’ll quote:

Traditional doctrine is also misleading in that it tends to promote the view that tense is necessarily an inflexional category of the verb. It is an empirical fact…that tense, like person, is commonly, though not universally, realized in the morphological variations of the verb in languages. Semantically, however, tense is a category of the sentence (and of clauses within a sentence as may be regarded as desentential in the full sense: cf. 10.3) (p 678).

And, this is my contention here. Empirical evidence points to non-temporality of the Koine Greek verbal system. As compared to the English, there is not a case in which a past tense can be non-past, or past + non-past, such as Mark 1:11 (as merely one example of a non-past).

Hi Craig,

An awful lot of water has passed under the linguistic bridge regarding our understanding of tense and aspect since Comrie and Lyons first started in the 60s. I pointed to the seminal work of D.N.S. Bhat as an example of such advances in my article on the HP. You are entitled to your opinion based on your what you’ve read, but you’ve not changed my mind on the matter. You’d need to move beyond this earlier work that Porter cites to more recent work. Having said that, I’ve never claimed that the non-temporal view of the verb in Greek is untenable, just that it offers an inferior account of the data compared to a mixed tense-aspect view. Tenseless languages behave entirely differently than we see in Greek. I wish you the best on your ongoing research into these matters.

Dr. Runge,

Thanks for your comment. In your opinion, then, is εὐδόκησα in Mark 1:11/Luke 3:22 a marked usage, given that it’s not (strictly) past tense in this context?

The nature of your question highlights the way in which we are talking past each other. You seem to be looking at the aorist indicative as though it necessary will convey a past temporal meaning if there is indeed any temporal reference in the Greek verb, right? But if you look at ti systemically, as Porter claims to do, what other choice would these writers have had for conveying a perfective action? Is there a non-past perfective option? No. The lack of a counterpart to the non-past imperfective or the non-past stative/perfect will necessarily lead to use of the aorist where perfective aspect was the higher value than the temporal reference. Does this mean that temporal semantics are necessarily absent, or cancelable in Campbell’s terms? No, Stephen Wallace made that clear citing a number of language in the 80s, and Bhat has demonstrated the same holds in a much wider variety of languages. I sought to demonstrate the fallacy of Porter’s use of this argument in my NovT article. Language make use of pragmatic accommodation to eliminate the need for things like a non-past perfective in Greek which would rarely be used. Although such anomalies offer apparently *logical* evidence against tense, it is not a linguistic argument. Yet it seems as though you continue to return to the same line of reasoning despite redirection. Again, you are entitled to your opinions, but it seems fruitless to continue the conversation here.

An entirely different matter is understanding your use and meaning of “marked.” It seems you are using it in Porter’s sense, as I do not see how one could consider the usage marked from the standpoint of asymmetrical markedness. If we are understanding the use on Greek’s terms rather than how it is rendered in English, the usage is quite straightforward: a simple perfective. It is a case where the value of aspect outweighed the value of tense within this mixed tense/aspect system.

I’d suggest directing questions to the b-greek forum on these matters, as that’s where such dialogues normally occur. Stephen Carlson is one of the moderators, and others like Mike Aubrey and Eeli Kaikkonen regularly respond to questions about tense and aspect. Please post any further comments to b-greek: http://www.ibiblio.org/bgreek/forum/viewforum.php?f=10&sid=13fb0efb0ccc637c8e764609ecc5ce72