I mentioned in a previous post that there are certain kinds of devices that work better in certain contexts than in others. In Mark 7:11-12, a fronted conditional clause was used to introduce the entity, whereas the synoptic parallel in Matthew 15:5-6 uses a left dislocation for the same context. This might make you think that the left dislocation is the “right” construction to use, then. Not so, dear reader.

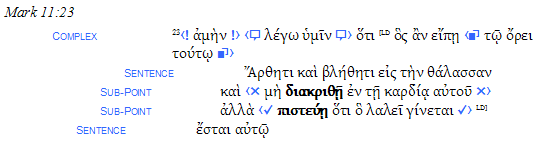

Different contexts call for different tools, even for the same discourse task of introducing a new participant. Take a look at this other minimal pair from Mark and Matthew. Mark uses a left-dislocation this time, and Matthew a conditional clause, but Mark’s version still comes across as more awkward than Matthew’s. Here is Mark 11:23:

Mark uses a “whosoever…” as the subject, with a complex series of statements describing exactly who the whosoever is. They say something to the mountain, they do not doubt in their heart, but believe. The one who fits this category, whatever he/she asks will have it done for him.

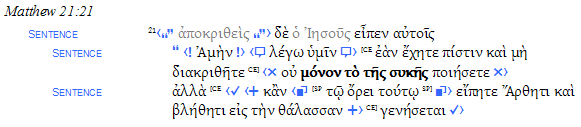

In Matthew 21:21, a conditional clause is used along with the second person instead of introducing a hypothetical entity using third person.

Using the second person eliminates some of the awkwardness present in Mark’s version. Rather than introducing a very complex person that must do several things before something else is done to them, the hearer/reader of Matthew’s version is confronted with a scenario. There is still some complexity, but it is easier to process since it is being applied to oneself rather than to some new and unknown entity.

So to answer the question about which strategy is best to introduce an entity, the only real answer is “It depends.” Contexts vary, hence why there is more than one way of accomplishing a discourse task. Attention to synoptic parallels can yield some great exegetical insights.

Isn’t grammar wonderful?

Grammar wnderful? Well, grammatical constructions can certainly make one wonder; τὸ θαυμάζειν, says Aristotle, is the wellspring of philosophy.

In my opinion, Mark 11:23 is not as awkward as it may seem (we very recently discussed this passage on B-Greek (my comments: http://lists.ibiblio.org/pipermail/b-greek/2009-July/049648.html). The ὅς ἂν + subjunctive construction is standard Koine for a generalization and is equivalent to ἐάν τις + subjunctive = “if anybody … ” =”anybody who … ” The admonition ἔχετε πίστιν in the immediately preceding verse sets the stage for the conditional construction of verse 23.

Matthew seems to have taken his cue from Mark’s ἔχετε πίστιν and used it to reshape the protasis and apodosis of the condition into the more colloquial second-person generalizing formulation: ἐὰν ἔχητε πίστιν καὶ μὴ διακριθῆτε … On the other hand, I’m not so sure that Matthew’s final one-word apodosis γενήσεται is as clear as Mark’s ἀλλὰ πιστεύῃ ὅτι ὃ λαλεῖ γίνεται, ἔσται αὐτῷ. Revision and careful proofing requires considerable effort.

It must be a sign of the Apocalypse, Carl, you claiming Markan wording is superior to Matthean! I agree that Mark strengthens the claim of Jesus by having both the positive and negative statements about belief. I will be talking about ways writers can mitigate commands in one of the next posts. One way is to move from the direct second-person to an indirect generic third-person. Thanks for pointing to the B-Greek dialogue.

It wasn’t my intention to say that the Marcan wording is superior to the Matthaean, apart from phrasing of the apodosis. Luke 17:5 is in fact more awkward than either of the parallels.

I know, I know, I just couldn’t resist the temptation so say something, tongue in my cheek and all that.